Apparently, Razor Burn is Capitalism’s Love Letter to Women.

How Advertising Invented a Problem to Sell You The Solution

If you’ve ever nursed a nasty case of razor burn, your enemy isn’t really your skin, your soap, or your shower temperature. Our antagonist is a very confident marketing executive in 1915 who realised he could double his revenue by convincing half the population that their own bodies are a problem that needs fixing.

We talk about shaving today as a “personal choice”. But that choice has history, and it’s a lot less personal, and a lot more engineered, than we like to admit. Even if, to be fair, some people genuinely enjoy it.

So how did we get here?

For most of modern history, razors lived exclusively in the men’s aisle, both literally and conceptually. Early Western ads were a testosterone-heavy fever dream of soldiers and clean-cut businessmen. Women weren’t just out of the frame; they weren’t even supposed to be in the building.

One question is raised. If women weren’t the original market for razors, why are they now the primary customers?

3 Players, Perfectly “Innocent” Coincidences

Before the industry stepped in with its “pink promises”, hair removal was done with tweezers, pumice, or sugaring.

It was an occasional grooming choice, not a hyper-routinised weekly maintenance schedule. Nobody was treating their legs like a NASA launch sequence requiring a 50-point safety check before leaving the house.

The shift didn’t happen because women suddenly woke up and hated their body hair. It happened because three powerful forces converged: fashion, media, and corporations.

All three industries simply followed the most innocent of principles.

Whatever makes money must be morally correct.

I. Fashion & the Great Exposure of Armpits

As hemlines crept up and sleeves vanished, parts of the body that had been politely hidden for centuries were suddenly out in the open.

And the moment a body part becomes visible, the commentary always follows.

Skin exposure created the opportunity.

II. Magazines as the Shame Machine

By 1915, magazines like Harper’s Bazaar began running ads warning women about “objectionable hair” under their arms, a phrase so dramatic it sounds like the armpit had committed tax fraud.

One ad claimed sleeveless dresses “necessitated” hair removal.

Important context: These magazines were, at the time, run almost entirely by men. The “beauty standards” being pushed, and the vocabulary of shame being used to sell them, reflected a very male, very conservative idea of what a woman’s body “should” look like.

Essentially, a group of men in suits looked at a sleeveless dress and realised they could turn “existence” into an “affront to society” if they just used the right typeface.

These standards created a crisis.

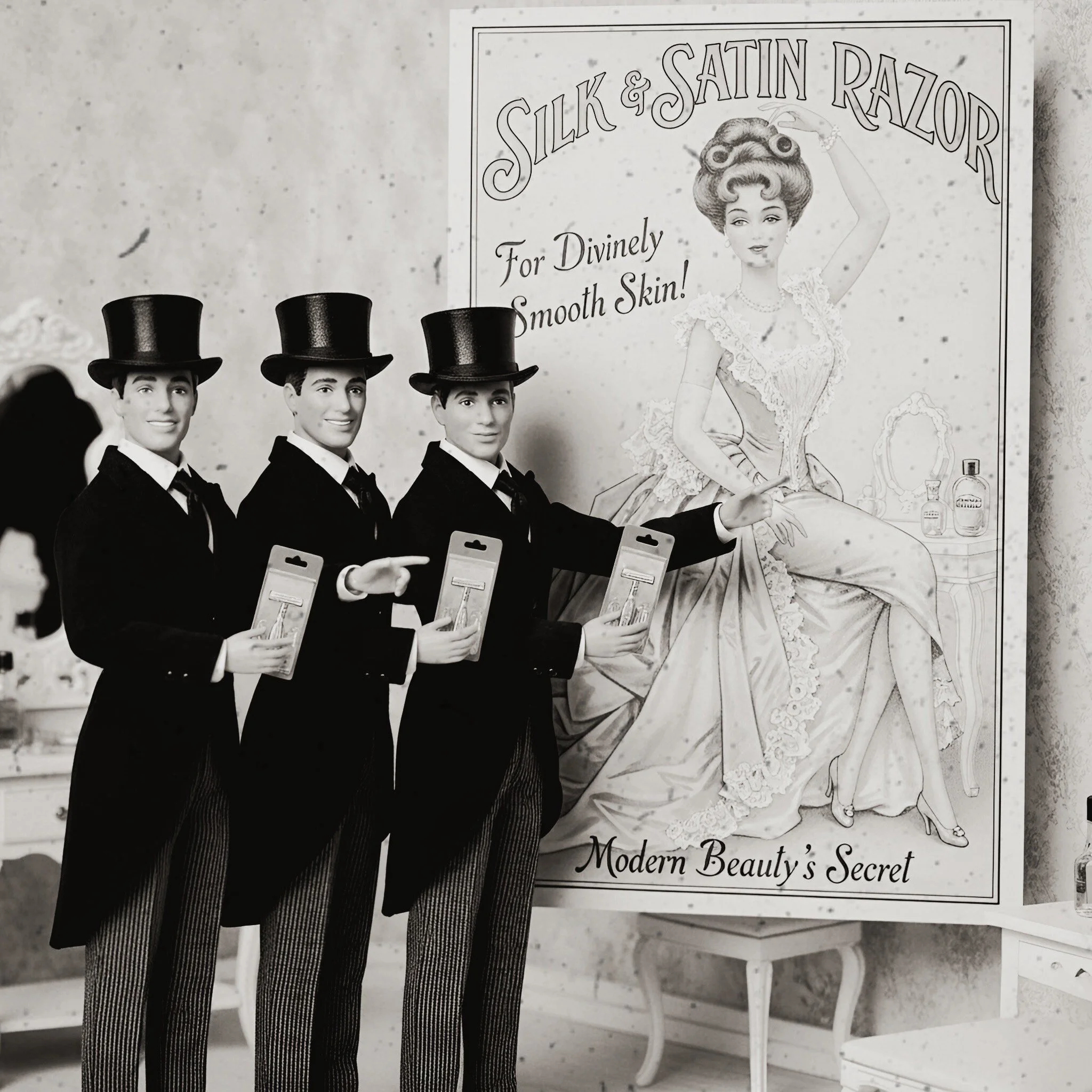

III. Corporations and The Milady Décolleté

Enter Gilette.

By the time the company launched its campaign in 1915, the groundwork was a warm handoff. Fashion exposed the skin, magazines provided the vocabulary of shame (“unsightly,” “unfeminine”), and all that was missing was a product.

The Milady Décolleté campaign linked smooth, hairless skin to modern femininity. And since the men’s market was capped, women were seen as an untapped gold mine.

Notably, they didn't even use the word “shave” at first; it was too masculine. They sold “refinement” and “smoothness.”

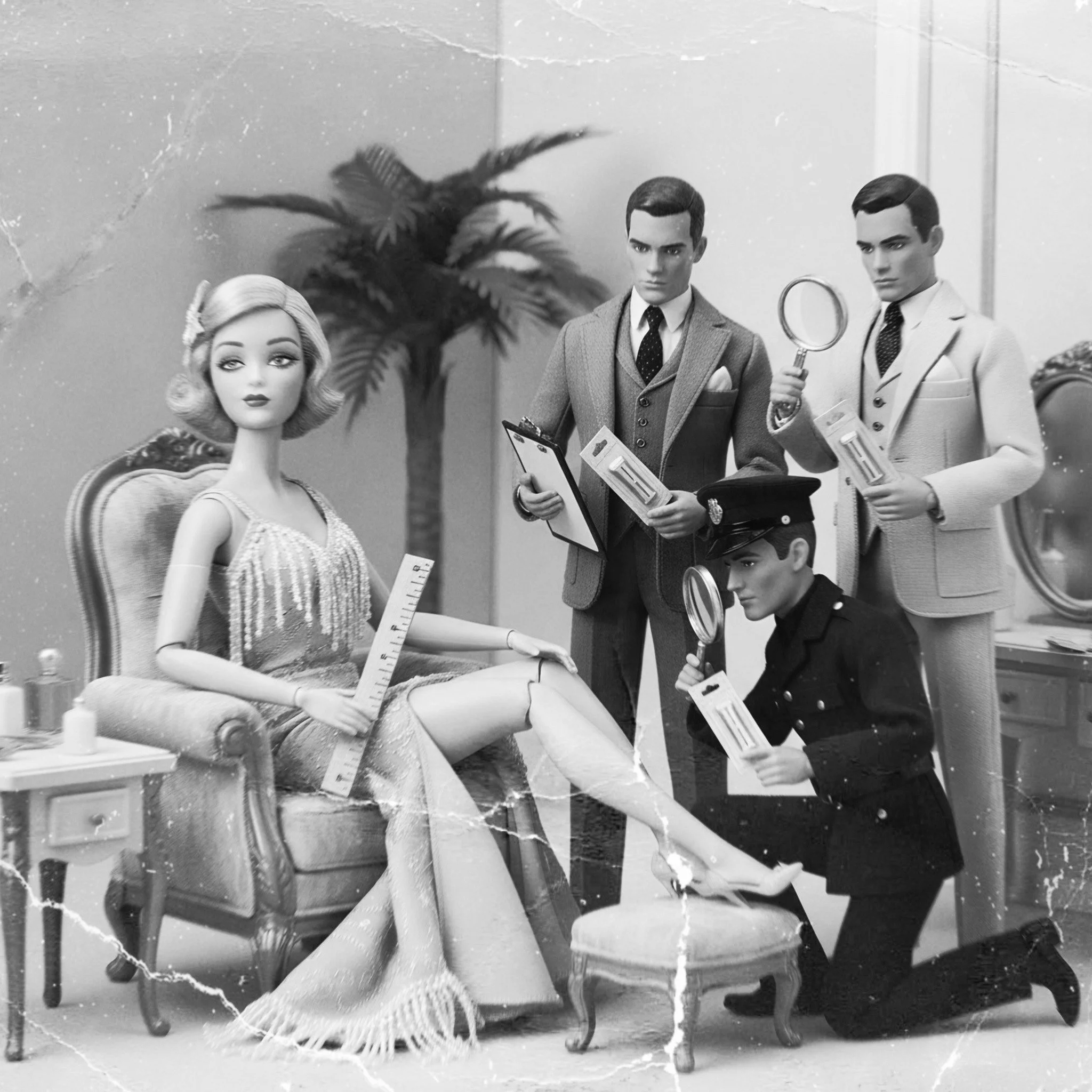

The 1920s-30s Propaganda Phase

This is where the habit truly stuck.

While the 1915 ads targeted the underarms, the following decades saw a slow, deliberate creep down to the legs. Magazines and beauty columnists spent twenty years associating body hair with a lack of hygiene and “old-world” sloppiness.

By the time the 30s hit, the “modern woman” was expected to be a smooth canvas.

What began as a manufactured crisis was becoming routine.

The WWII Catalyst

If 1915 lit the match, World War II poured gasoline on the fire.

When Uncle Sam requisitioned the nylon to make parachutes, stockings vanished from shelves. Bare legs weren't a stylistic choice anymore; they were the only option.

And because women couldn't legally or socially wear pants yet, their legs were constantly on display. Skirts were the uniform, stockings were gone, and the razor was the only thing left to “fix” the exposure.

What had been a trend became a necessity.

The Global Domino Effect

This whole circus began in the United States, the epicentre of 20th-century marketing. Once the U.S. successfully branded “smooth legs = civilisation”, they exported it alongside Hollywood movies and fast food.

The “Shaving Vortex” spread like a contagion, claiming victims in roughly this order:

USA as Ground Zero

By 1917, Gilette’s own annual report admitted the women’s market was pursued because the men’s had reached “steady replacement phase”.

UK & Canada as the “copy-paste” markets

In 1922, British Vogue ran the same “objectionable hair” ad copy, word-for-word. By the early 1950s, UK pharmacy giant Boots began aggressive cross-promotions, placing razors directly next to “modern” American-style beauty products to capitalise on the “Hollywood look” women saw in cinemas. Sales tripled within five years.

Western Europe & Post-war Americanisation

As Hollywood films, fashion magazines, and beauty products flooded France, Germany, and Italy in the late 1940s and 1950s, the smooth-skin aesthetic came with them.

Some testimonies from German women confirm that armpit shaving was uncommon in the 1940s but “began to catch on in the 1960s” as “a delayed post-war copy of American Practices.

The Rest of the World (Delayed until the arrival of TVs and global ad budgets)

Japan offers a particularly perverse example.

In the 1920s, the exact moment American Ads were branding shaving as feminine virtue, Japanese culture associated body hair removal with prostitution. Shaving marked you as a sex worker, not as a respectable woman.

Then Western fashion arrived.

Jun’ichiro Tanizaki’s novel Naomi (1920s) captures the shift. His protagonist shaves her underarms and explains, “It would be rude” to wear Western clothing without doing so.

The true globalisation didn’t hit until the late 1960s and 1980s, when TV brought American beauty standards into homes across Asia, Latin America, the Middle East, and Africa.

What began as a niche American marketing ploy became a worlwide norm.

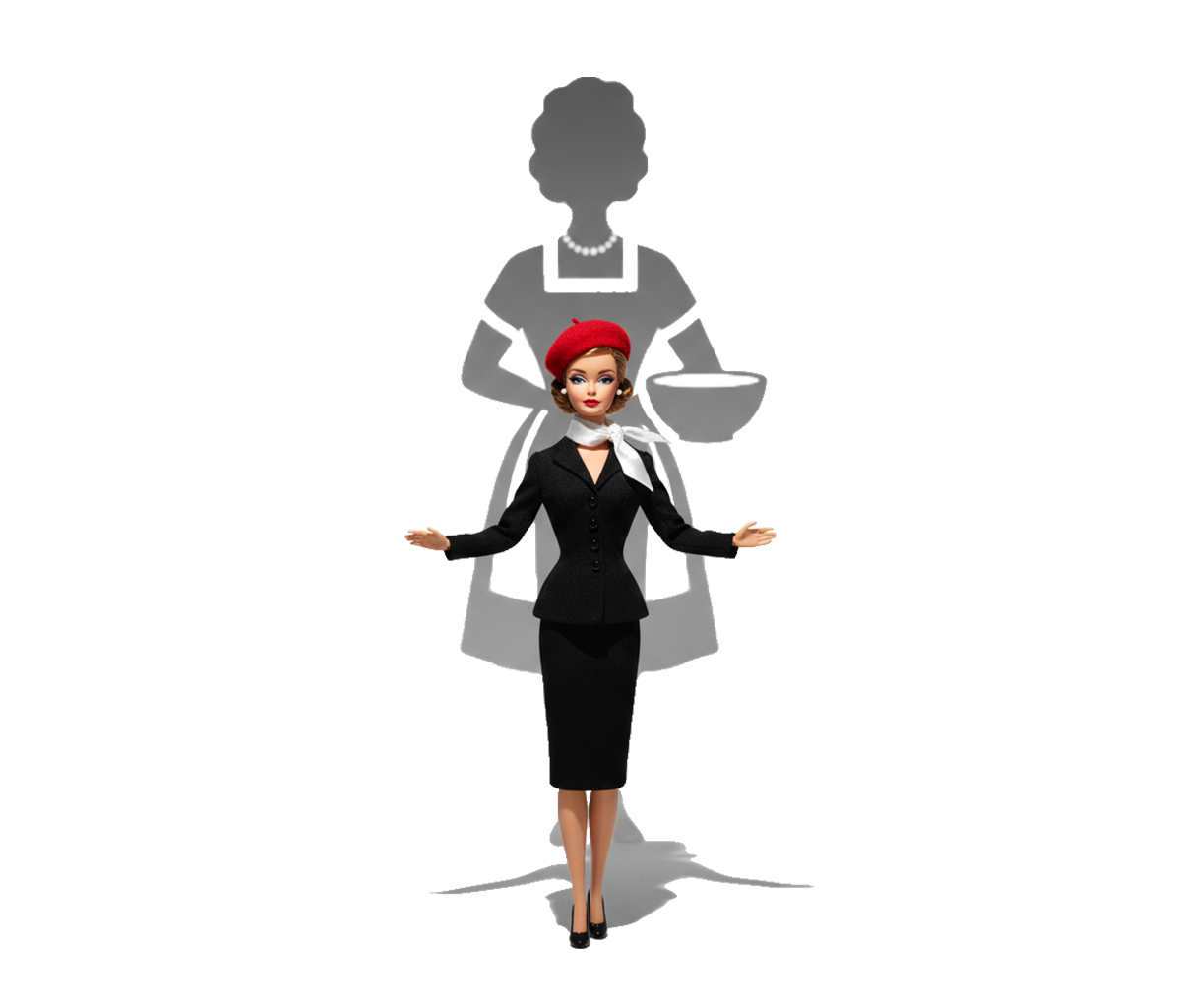

There is a profound, cosmic comedy in the fact that we consider shaving a “personal choice” today.

In the 1940s, women often couldn't own property without a male cosigner, but they were “trusted” with a razor and the lifelong responsibility of ensuring their legs didn't offend the nation.

Society essentially said:

“No rights for you, but please do maintain your lower limbs to a standard we invented ten minutes ago.”

And that is the real mystery resolved. Not why women shave, but how a made-up standard became so deeply embedded that it now masquerades as instinct.